Adoptee searches are fraught with uncertainty. Searching for blood relatives requires a certain amount of guts, grit, patience and tolerance for pain and discomfort. Brace yourself. Expect the unexpected. You have no way of knowing what you’re in for.

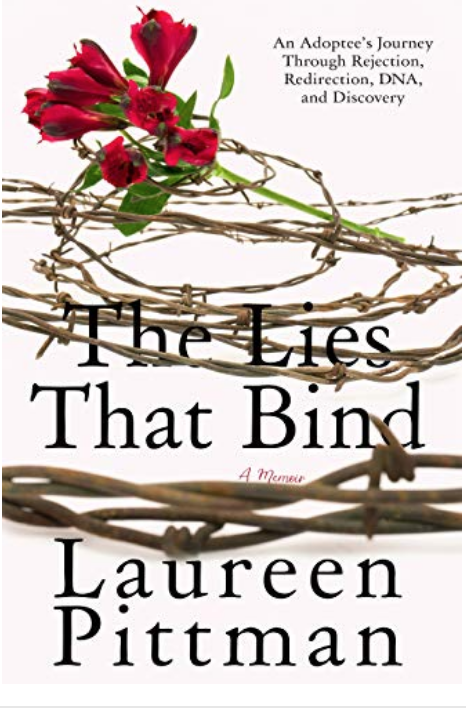

And so the adventure began for adoptee Laureen Pittman, who shares the ups and downs and twists and turns she encountered in an engaging memoir, “The Lies That Bind” (2018: Amazon KDP).

Pittman’s remarkable story begins with her birth in a California women’s prison in 1963. Her birth mother was an unmarried 18-year-old woman serving time on drug charges.

As an infant, Pittman was adopted by a married couple and encouraged to think of adoption as nothing out of the ordinary. Being adopted doesn’t matter, or so she was told.

Adoptee Search Begins With Birth Mother’s Name

By many accounts, her childhood in sunny California was typical. Pittman grew up with an older brother, who was also adopted. She didn’t begin the search for her biological family until she was a young woman. Her adoptive parents provided her with the birth mother’s name and with that information, Pittman was on her way to discovering the truth, in bits and pieces.

She hired a private investigator, who dug up the non-identifying information about her birth mother and birth father. Later, she would learn that some of the “facts” in the non-identifying information were falsehoods.

Though Pittman approached her birth mother, Margaret, respectfully, Margaret rebuffed her overtures. The birth mother had created a life that didn’t acknowledge the baby she had relinquished. Margaret covered up Pittman’s existence. She had never told her mother about the pregnancy.

Margaret resented the intrusion, feeling as though her privacy had been violated.

In letters to Pittman, the birth mother spoke glowingly about her successes in life and never inquired about Pittman or her family. Hurt by her birth mother’s rejection, Pittman ended the correspondence with Margaret.

DNA Test Identifies Adoptee’s Birth Father

Years later, through an astonishing stroke of luck, Pittman would find her birth father. His name popped up as a close match on Pittman’s DNA test results. Through emails and Facetime, Pittman and her birth father, Jonathan, got to know one another and a warm relationship developed.

Pittman would not discover any details about her conception. Suffice to say, Jonathan and Margaret conceived Pittman in the drug-tinged, psychedelic ‘60s. Jonathan had no recollection of Margaret, had no idea he had fathered a child.

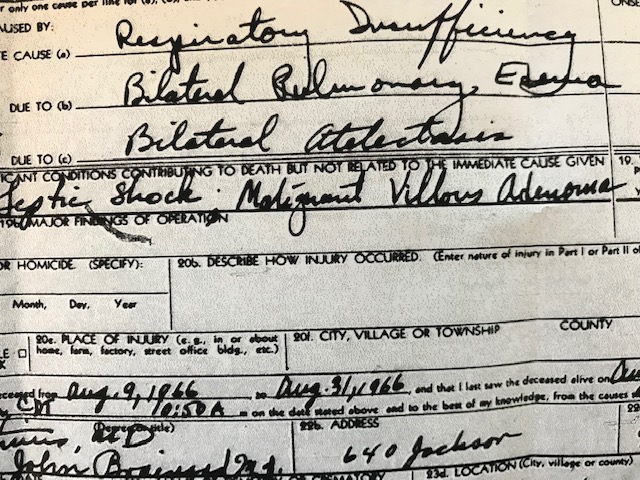

He took a DNA test not with the hope of finding a long lost biological daughter but for answers to nagging questions about his father, who died when Jonathan was 6. Jonathan’s secretive mother had refused to answer his questions even as she lay dying.

The story moves in an unexpected direction, as Pittman and her father work to unravel the mystery.

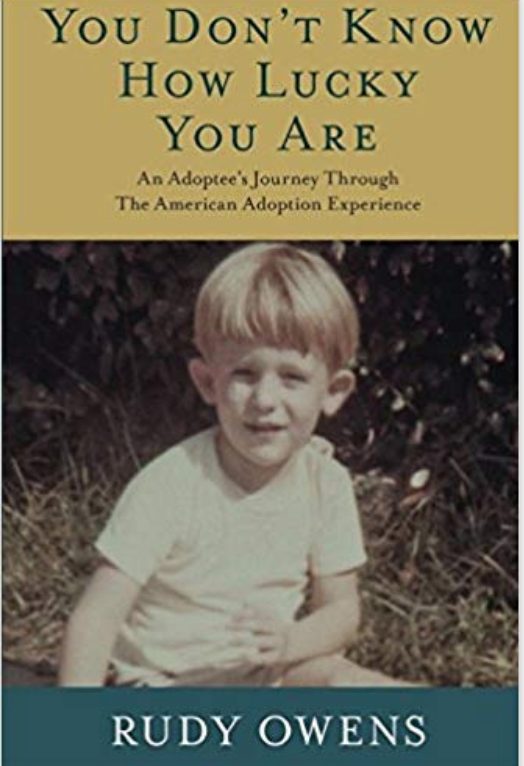

The book resonated with me on a personal level. Like me, Pittman was born in the 1960s, when people concealed out-of-wedlock pregnancies and adoptions.

Adoptee Searches Uncover Family Secrets

While Pittman is not a late discovery adoptee, she and her father Jonathan uncovered long-buried family secrets, much like adoptees who discover their hidden adoptions later in life. (My parents, Claire and Bob, went to their graves without telling me I was adopted, leaving not so much as a single piece of adoption paperwork behind. They kept the adoption hidden from me and my sister, Melissa, also adopted. Through Melissa, I found out about my adoption a few years after my father’s death.)

With sensitivity, “The Lies That Bind” examines issues that are important to adoptees. In recounting the painful experience of being rejected by her birth mother, Pittman explores adoptee rejection, one of the perils adoptees can encounter when they find biological parents or other relatives who want nothing to do with them.

“The Lies That Bind” is a thoughtful book that adoptees can relate to and a quick read. I finished it over a weekend.